Xen and the Art of Virtualization

About

This summary discusses x86 virtualization in VMware’s Xen, a resource-managed monitor that enables server consolidation, co-located hosting facilities, distributed web services, secure computing platforms, and application mobility.

Key Terms

- Hypervisor- A.k.a. virtual machine monitors, an abstraction that creates and runs virtual machines. In this summary we use monitors for brevity.

- XenoLinux- VMware’s Linux port that is compatible with Xen?

Background

There’s a few challenges when partitioning a machine to support concurrently executing guest operating systems:

- VMs should be isolated from each other (trust-issues).

- It’s desired to support multiple kinds of operating systems due to the benefits and popularity of multi-platform applications.

- The virtualization needed to achieve such partitioning should introduce little overhead.

Unlike their competitor, VMware’s ESX for example, Xen requires a guest VM, e.g. XenoLinux, to sit between the monitor and guest operating systems. It exports an ABI identical to a non-virtualized Linux OS.

Full Virtualization Woes

A traditional monitor exposes a virtual hardware interface that is functionally identical to the underlying machine. Full virtualization provides the benefit of not having to modify the guest OS binaries, however there’s a few drawbacks, if x86:

- Full virtualization support was never apart of x86 architecture design.

- Some instructions need to be intercepted by the monitor and handled. Without the sufficient privilege, they may fail silently instead of trapping correctly.

- Efficiently virtualizing x86 is difficult.

E.g., the ESX server dynamically rewrites some of the hosted machine code to insert traps when monitor intervention is needed. Since all non-trapping privileged instructions must be caught and handled, this dynamic translation is applied to the entire guest. This results in high-cost, update-intensive operations such as creating a new application process.

Xen avoids the drawbacks of full virtualization by providing a monitor that is similar to the underlying hardware- paravirtualization.

Paravirtualization

A drawback of this approach is requiring modifications to the to the guest OS, but not guest applications due to leaving the ABI pristine.

Xen paravirtualization is summed into these few design principles:

- Users won’t use Xen if ABI modification is required.

- Need to support complex server configurations in a single guest OS instance to support multi-application operating systems.

- Can’t have high-performance and strong resource isolation on x86 unless you paravirtualize.

- Completely hiding resource virtualization effects from the guest operating systems is risking correctness and performance.

VM Interface

Memory Management

This is the most complex part of the interface, requiring monitor mechanisms and guest OS porting.

One such guest OS modification, or port, is the need to relinquish write access to page tables it creates to service things like creating a new process. This is required to register such page table with Xen which handles subsequent updates.

CPU

Inserting the monitor below the OS violates the assumption that the OS has the highest privilege in the system.

This is mitigated on x86 since it supports four privilege levels (rings) via hardware, 0 to 3 with the latter being the least privileged. On a typical OS, its kernel executes at ring 0, with user applications running in ring 3. It’s rare that a typical OS runs anything at ring 1 and 2- such operating systems are ideal to run on Xen since their kernel can be run at ring 1 while preserving equivalent access control.

I presume Xen runs at ring 0. Any guest OS attempting to execute privileged instructions will be faulted since only Xen occupies such privilege.

Safety is ensured by checking exception handlers presented to Xen, which only checks that the handler’s code segment doesn’t want to execute in ring 0.

Device I/O

Full virtualization has the overhead of fully emulating existing hardware devices. Instead, Xen exposes a set of simple device abstractions without sacrificing protection and isolation.

I/O is transferred in and out of each domain through Xen, made possible with the following data structures:

- Asynchronous buffer descriptor rings

- Shared memory

This allows Xen to transfer data vertically in the system, but also allowing Xen to validations.

Cost of Porting OS to Xen

Not much- 1.36% and 0.04% of total x86 code for Windows and Linux needed to be modified for porting.

Controls and Management

Xen aims to separate policy and mechanism wherever possible.

Complex policy decisions like admission control is better administered on a guest OS rather than in the privileged monitor.

Regarding the figure above:

- Domains are created at boot time and is permitted to use the control interface.

- The control interface provides mechanisms to create and terminate other domains, control domain scheduling parameters, physical memory allocations, and access to machine disk and network devices.

- The initial domain,

Domain0, hosts the application-level management software.

Detailed Design

Thought experiment 2 might be covered here.

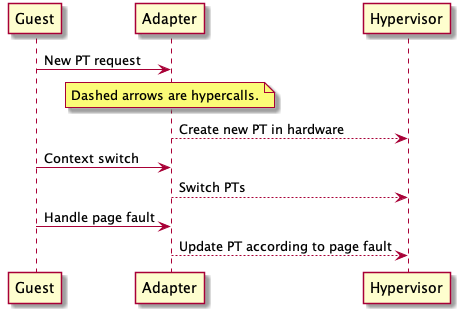

Control Transfer: Hypercalls and Events

Hypercall

Since the guest knows about the monitor, some of the burden of efficient mapping can be shifted to the guest. The PPN to MPN mapping is now managed by the guest via the hypervisors hypercall API.

This provides a mechanism for guests to synchronously call into the monitor.

Events

This mechanism provides asynchronous communication from Xen to the guest. It replaces conventional device interrupt communication and allows lightweight notification of important events.

These are analogous to Unix signals. The guest registers their call-back event handler to respond to the notifications from Xen and resetting the set of pending events.

Data Transfer: I/O Rings

Async Ring Transfer Structure

Since the monitor sits between the guests and I/O devices, Xen needs a data transfer mechanism to move data vertically through the layers.

Two big brain mechanisms shape this I/O transfer mechanism: resource management and event notification. The ring structure in the figure provides sufficient generic support for a number of different device paradigms.

Subsystem Virtualization

CPU Scheduling

Xen uses Borrowed Virtual Time scheduling algorithm for its work-conserving and low-latency wake-up properties for waking up domains when they receive an event. This is important for virtualized sub-systems needing to run in a timely fashion, such as TCP.

Virtual Address Translation

VMware gives each guest OS a virtual page table not visible to the MMU. It then has to trap access to the virtual page table, validate updates, and propagate changes between the MMU and shadow page tables. This increases the cost of certain guest OS operations, with the benefit of contiguous physical memory illusion.

Xen only needs to be concerned with page table updates so that the guest doesn’t make unacceptable changes. This avoids the overhead and complexity of VMware’s shadow page table.

Physical Memory

Like VMware’s ESX server- Xen uses device ballooning to adjust the domain’s memory usage by passing pages back and forth between Xen and XenoLinux’s page allocator.

This driver harnesses existing OS functions which simplifies the Linux porting effort. With paravirtualization, the driver can be extended to handle fault-handling mechanisms in the guest OS directly.

Network

Xen provides two network abstractions:

- Virtual firewall-router (VFR)

- Virtual network interfaces (VIF), logically attached to the VFR- Looks like a network interface card and has two I/O rings for transmission and receiving.

To transmit a packet, the guest just enqueues a buffer descriptor onto the transmit ring. The Xen copies and handles the descriptor, performing security checks along the way. Xen uses round-robin scheduling to ensure fairness.

Disk

Only Domain0 has direct unchecked access to physical disk. All other domains access disk via virtual block devices (VBD) managed by Domain0. Upon disk request, Xen inspects the VBD metadata and produces the corresponding sector address and physical device. This lets Xen perform permission checks.

Performance

We summarize some of the performance results with Xen, VMware Workstation, and native Linux here.

- Xen outperforms VMware in processing time by a wide margin.

- Xen way outperforms VMware in context switching time.

- Xen underperformed against VMware in terms of bandwidth.

- Xen outperforms VMware in file and VM system latencies.

- Xen and VMware have similar levels of isolation, although VMware sacrifices absolute performance to achieve this.

Virtualization Motivations

- Grouped physical servers may suffer from under-utilization, why not consolidate them as VMs on one server with little performance penalty?

- Consolidating many servers into one can simply and reduce management cost.